Innovation, Culture, and War

August 28, 2025

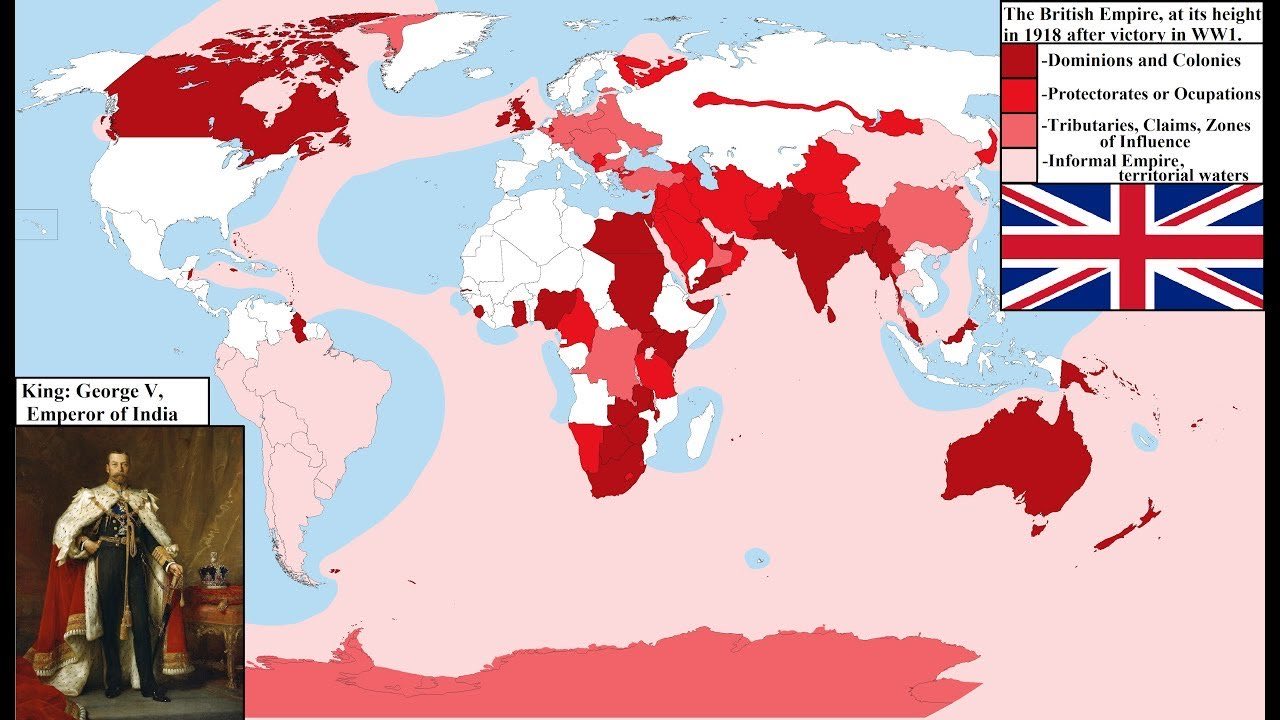

The Largest Empire In History

Map of the British Empire in 1918

At its height, Britain ruled the largest empire in history, aptly named "the empire on which the sun never sets". This global reach was possible because the Royal Navy commanded the seas. The navy was the foundation of Britain's power, protecting its trade routes, projecting influence, and deterring rivals. How did the British Royal Navy operate? How did it react and evolve in the face of innovation?

Doctrine, Strategy, and Tactics

Before World War I, The British Navy operated based on the following combination of Doctrine, Strategy, and Tactics:

Doctrine: The guiding philosophy of the Royal Navy: command the seas by maintaining a fleet larger than the next two navies combined.

Strategy: Protect shipping lanes, enforce naval blockades, and use decisive fleet engagements when possible.

Tactics: Rely on line-ahead formations and mixed armaments—heavy and medium-caliber guns—for flexibility in battle.

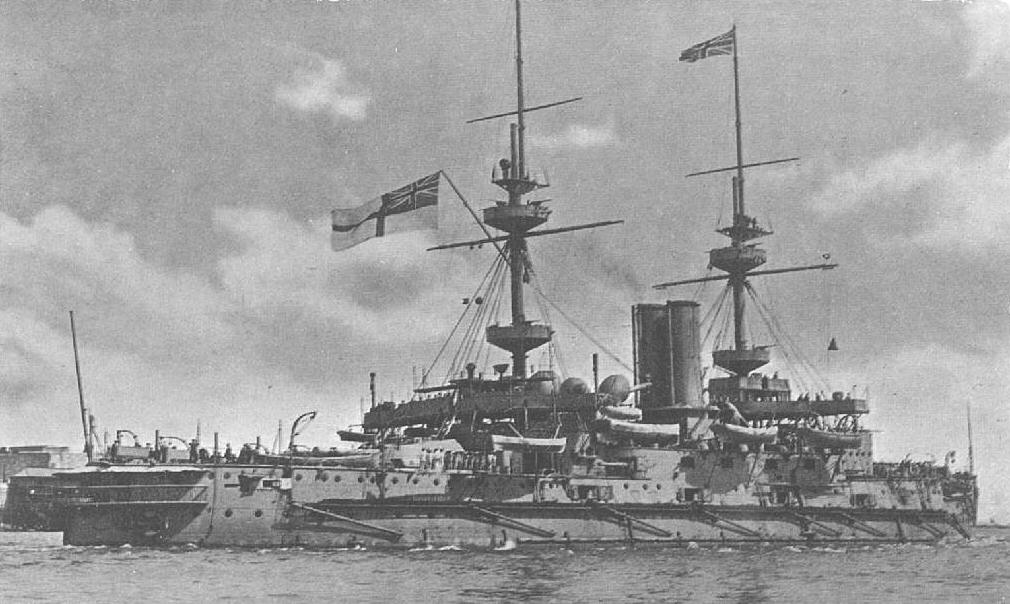

HMS Majestic, Flagship of the British Navy in 1905, boasting a mixture of 12, 6, and 3-inch guns.

Picture yourself among the main battery crew aboard Majestic, flagship of the British Royal navy in 1905. Hitting a target seven miles away without computers required extraordinary skill, using mechanical fire-control tables, gears, dials, communication from spotters, and a deep understanding of wind, range, and ballistics.

Shell splashes from mixed armament salvos

In the chaos of naval battle, gunnery depended heavily on observing the splashes of shells striking water around the target. Spotters had to adjust aim based on where shells were landing. But with a mixture of calibers—12-inch, 6-inch, and 3-inch—the splashes were indistinguishable. Was that plume from a heavy shell, a medium one, or a small one? No one could be sure.

That meant each gun group required separate fire-control calculations—different tables, different ranges, different spotting adjustments. The result: precious seconds lost in correcting aim, while the enemy's guns found their mark.

A New Type of Battleship

The HMS Dreadnought circa 1906-1907

The British solved this problem with radical simplicity: an all-big-gun design. The HMS Dreadnought carried ten 12-inch guns, supported only by light anti-torpedo armament. This meant all main batteries could share a single firing solution and deploy overwhelming firepower at maximum range.

Coupled with her turbine engines, which gave her unmatched speed (about 21 knots, faster than any contemporary battleship), the HMS Dreadnought changed the game.

"She makes all other battleships afloat look like medieval curiosities." - The Times

Overnight, every mixed-armament battleship (even those in the Brisith Royal Navy) became obsolete, relegated to the category of "pre-dreadnought".

"If you don't cannibalize yourself, someone else will." - Steve Jobs

The Arms Race

The impact was immediate. HMS Dreadnought literally redefined the word battleship. By 1914, nearly 100 dreadnoughts had been built worldwide: 29 by Britain, 17 by Germany, and others by rising powers like the United States.

This triggered a naval arms race that reshaped international relations. Britain's dominance forced competitors to spend heavily just to keep pace. By the outbreak of World War I, dreadnoughts symbolized not just naval power but national prestige.

Influence and Legacy

Despite their power, dreadnoughts rarely got to use all those big guns. The only major engagement that significantly involved dreadnoughts, the Battle of Jutland in 1916, ended indecisively. But their true power was psychological and strategic. They served as deterrents, shaping strategy and diplomacy as much as battle itself.

The influence of the HMS Dreadnought extended well into World War II, long after the design had been eclipsed by a new innovation: the aircraft carrier. Yet naval culture was slow to adapt. For decades, battleships remained the ultimate symbol of national prestige and military might.

Both the Japanese and German navies illustrate this cultural inertia. Japan poured immense resources into the Yamato and Musashi, the largest battleships ever built, because its naval doctrine, Kantai Kessen, advocated for a decisive battle and saw battleships as the "heart of the fleet".

But by the 1940s, naval warfare had changed again. Aircraft carriers extended striking power hundreds of miles beyond the horizon, rendering even the most heavily armed battleship vulnerable. The Yamato and Musashi were sunk by swarms of carrier-based aircraft. The Bismarck was crippled not by gunfire, but by torpedo bombers that disabled its rudder.

These super-dreadnoughts were engineering marvels—and yet, later, they became liabilities. One can't help but wonder how differently the war in the Pacific might have unfolded if Japan had invested those resources into carriers rather than clinging to the prestige of the battleship.

The lesson is striking: culture has momentum. Once the battleship had become the yardstick of naval power, nations struggled to pivot—even when evidence showed the paradigm had shifted. That momentum worked for Britain in 1906, when the HMS Dreadnought embodied innovation. But by the 1940s, the same momentum worked against Japan and Germany, locking them into a doctrine already rendered obsolete.

Lessons for Today

The story of HMS Dreadnought is more than naval history—it's a case study in how bold simplification can revolutionize an entire field.

But it's also a cautionary tale: when technology shifts, culture must adapt or risk being left behind, no matter how mighty your "battleships" once were. It demonstrates how the power of cultural momentum can be both a strength and a trap.